Title: “Protection against the Evil Eye? Votive Offerings on Armenian Manuscript Bindings”

Author: Dr. Sylvie Merian, Reader Services Librarian at the Morgan Library

Summary: Dr. Sylvie Merian offers various possible explanations for the hodgepodge of items affixed to Armenian Gospel books and sacred texts.

About the piece: Article, 2013, 26 pages

Access the piece here.

Read this article if you want to learn more about:

- the uniquely Armenian practice of affixing objects to sacred books as votive offerings. According to Merian’s study, no other culture does this. Offerings are usually made to icons or statues, but not manuscripts or printed books (p. 81).

- possible explanations for these objects such as warding off the evil eye and protection against illness or catastrophe.

Some interesting points:

- The Evil Eye

- The original belief of the Evil Eye, popular in the Near East and other regions, is that one possesses an evil eye and can unintentionally provoke harm unto others, often triggered by envy (p. 57).

- In the Near East, this often takes the form of a glass, blue eye. Why? One theory is that in a land awash with brown eyes, evil was brought by foreigners and invaders, often with blue eyes (p. 63).

- Armenian belief in the Evil Eye dates back centuries and is written about by Movses Khorenatsi. The belief in protective talismans was so widespread that numerous church documents were written denouncing the practice of using them to ward off evil.

- The importance of the Gospel (the first four books of the New Testament) in Armenian Christian tradition: It is read as part of the Divine Liturgy, handled with cloth as a sign of respect. In short, it is a venerated object. She writes, “the custom of Armenians prostrating themselves before the Gospel and kissing it has been attested to since the 7th century.” (p. 53)

- Some Gospel books are said to have miraculous powers and are still visited as sites of pilgrimage for believers (p. 56).

General Summary

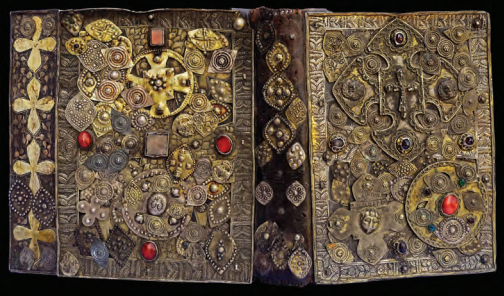

Adding precious metals in the shape of Christian imagery is a common practice dating back to the 4th century. Gold, silver, pearl, ivory and other materials have been found affixed to sacred manuscripts, often in the shape of crosses, crucifixions, the symbols of the evangelists and biblical events. They are meant to both demonstrate God (and its owner’s) power and wealth, which is why they are made of such valuable material. The earliest known Armenian example dates back to 1255.

While this is a widespread practice throughout the Christian world, and not unique to Armenians, according to Merian, what is wholly unique to Armenian culture (with only two extant examples found elsewhere) is the addition of “bizarre objects” to sacred texts.

These objects range from jewelry to coins and charms. They are attached in an often haphazard manner with no thought for design and no intention of displaying wealth or ostentation, unlike the above-mentioned examples. Merian’s article is an effort to elucidate why these objects are affixed to sacred Armenian manuscripts.

Merian then goes through several possible explanations for the objects including protection from the Evil Eye and offering of thanks for miracles. The random placement of the objects attests to this, as does the fact that they are not of precious metals, but materials more available to villagers.

Another possible explanation is that the objects were placed there to protect the book itself from harm. This hypothesis begs the question of why a venerated object, believed to have miraculous powers needed protecting? To which Merian reminds the reader of the time and location Armenians were living in and the frequently hostile situations in which they found themselves, such that even sacred texts were not immune from pillage and abduction.