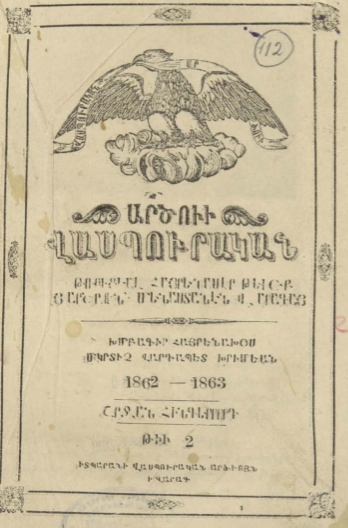

Title: Handes Hakarakuteants: Hayots Grabar ev Ashkharabar Lezuats

Summary: A tongue-in-cheek conversation between Classical Armenian and the vernacular.

Author: Garegin Srvandsiants

About the piece: Published in Artsvi Vaspurakan in the second edition of 1862/63, pages 51-61

You can access the piece here.

Read this article if you want to learn more about:

- An important, contemporary discussion happening within the Armenian community of the Ottoman Empire

- The “Artsvi Vaspurakan” publication

Some interesting points:

- Though the article is one of few instances of comedy or satire in Artsvi Vaspurakan, the subject is quite in line with what the publication is known for: providing rural Armenians with articles that will educate them and keep them abreast of important events and contemporary discourse happening in the world

- Though Artsvi Vaspurakan (Արծուի Վասպուրական) was printed by the famed cleric Mkrtich Khrimian Hayrik, the article itself was written by his student, also a cleric, Garegin Srvandsiants, who, though less known than Hayrik, played a valuable role in what would later be dubbed, “The Armenian Awakening.”

About the Eagle of Vaspurakan

Mkrtich Khrimian Hayrik published the “Eagle of Vaspurakan” from 1855 to 1864, initially in Constantinople, but soon moved publishing to Van in 1858. The purpose of the periodical was two-fold:

- To educate the Armenian rural population in the eastern villages of the Ottoman Empire. Khrimian and his students printed articles ranging from Armenian history and geography to the scientific explanation of earthquakes and a translation of French author Alphonse de Lamartine.

- To educate the Armenian urban elite of the dire situation of the Armenian homeland.

Khrimian also published an offshoot of the “Eagle of Vaspurakan” called the “Eaglet of Taron” from 1863 to 1865.

This particular article was written by the priest Garegin Srvandsiants, Khrimian’s most prominent student. Srvandsiants was a fierce nationalist and prolific writer who was also first to commit the Armenian legend, The Daredevils of Sassoun (Սասնայ Ծռեր), to writing. Prior to his work, the legend existed only through oral transmission.

Classical Armenian vs. Vernacular Debate

Srvandsiants’ article is structured as a fictional conversation between Grabar (Classical Armenian) and Ashkharabar (vernacular), each extolling its own virtues while simultaneously deriding the other.

For example, at one point in the article, Grabar and the vernacular have been sparring for a few pages and grabar responds to vernacular’s claim that its time has passed.

Grabar says, “I’ve gotten old and my time has passed? Disgrace. Do you know who I am? Christ’s holy Gospel and hymn are born and baptized with me.”(հնացայ ու անցա՞յ, հըյ․․․անշնորհք, գիտե՞ս ով եմ ես․․․Քրիստոսի սուրբ Աւետարան ու շարական ինձմով են ծնած ու կնքուած:)

To which the vernacular replies simply, “May God illuminate your soul.” (Աստուած հոգիդ լուսաւորէ:)

It is a marvelous article, not just for its imaginative structure and biting humor, but because it brings a relevant contemporary discussion directly to the rural Armenian. Though Grabar had its uses as the literary language, it became more and more incomprehensible to the Armenian masses and the varying dialects which were developing and was mostly on its way out by the 19th century.*

Interest in Classical Armenian was temporarily revived by Mikhitar of Sebastia, the Catholic Armenian monk and founder of the eponymous order, “yet public illiteracy in general and ignorance of Classical Armenian in particular forced [Mkhitar] and other pragmatically-minded contemporary reformers to resort to realistic ways of communicating with the increasingly larger circles of readership.** By 1891, to address the waning ability to communicate in Grabar, the Patriarchate of Constantinople formally authorized instruction in Modern Western Armenian.** Thus, though the death knell of popular usage of Grabar had long been sounded by the time Srvandsiants’ article was published, it was still a pertinent subject of discussion and one that may not have been broached in the eastern provinces.

The article is especially interesting because it was written by a clergyman for the publication of the man who would hold the position of both Patriarch and Catholicos, the two highest positions in the Armenian Apostolic Church. This flies in the face of the trite assertion that the church has been a crippling agent in Armenian history, always backwards or, at best, staunchly conservative. Besides the existence of such a progressive publication with a clergyman standing at its helm, this article illustrates that even sacrosanct issues such as Grabar, the language in which the Divine Liturgy is composed and conducted, were part of the discourse, a discourse initiated by a cleric. Khrimian himself first wrote in Grabar and was a supporter of its use, but eventually acceded to use of the vernacular because he too recognized that that was the only language which would reach his beloved flock.

This is but one example of the type of thought-provoking pieces published in the Eagle of Vaspurakan. Collectively, the articles give the reader insight to the life of the rural Armenian villager, what was important to them, and also what was happening in both the Armenian millet and beyond it.

The final conclusion of the article? “To Grabar, respect and immortality. To the vernacular, life and progress.” ( Գրաբառին միշտ յարգանք եւ անմահութիւն։ Աշխարհաբառին կեանք եւ յառաջադիմութիւն։)

A just compromise.

Further Reading:

* Cowe, Peter. “Medieval Armenian Literature and Cultural Trends,” edited by Richard G. Hovannisian, 293-326. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

** Bardakjian, Kevork. September 17-26, 2011, Yerevan, paper on “The rise of Classical, Middle and Modern Western Armenian literary standards,” at an international conference marking the 1650th anniversary of Mashtots and the opening of the new wing of the Matenadaran, organized by the Matenadaran.

All issues of The Eagle of Vaspurakan are available here.